Software Engineering Weekly | Dec 7: Investigating Regex Parsing

SEW (Software Engineering Weekly) is a blog series dedicated to exploring and sharing insights from the world of software engineering. Each week, I take a deep dive into a specific article, blog post, or research paper, providing a comprehensive summary and analysis. This series aims to keep myself updated on the latest trends, best practices, and innovative ideas in the field of software engineering. By documenting what I learn, I aim to keep myself accountable in the long run.

Investigating Regex Parsing

Greetings. I’m gonna cheat a bit this week, write a longer blog and take a break next week. Sounds fair? We’ll choose to ignore that I haven’t published anything for over a month (hey, I had endsems!). Anyways, today’s topic is going to be Regex Parsing. Before you scoff at me that who needs to learn Regex when you can just ask ChatGPT or Llama3.1 (I’ve been running models locally :)) to give you a RegExp for whatever needs to be parsed - yes. I’m quite aware of that fact. But, to quote Russ Cox - the technical lead at Google behind Golang.

Historically, regular expressions are one of computer science’s shining examples of how using good theory leads to good programs. Today, regular expressions have also become a shining example of how ignoring good theory leads to bad programs.

Bring down the pitchforks, there’s more to Regex than you think - and this blog will uncover it all, well - some of it, and point you towards better well-documented resources wherever possible.

Note: the article treats regex = regexp = regular expressions. If you’re interested in this debate (I’m certainly not), read this.

RegExp/Regex - a historical POV

RegExp or Regular Expressions - sequence of characters used to match a pattern in string searching. Popularized by Ken Thompson (who also worked on Golang) through the use of regular expressions in Unix, they were eventually standardized in the POSIX standard. Perl added more complicated expressions through its TCL library (see New Regular Expression Features in TCL8.1). Eventually, inspired by Perl, Perl Compatible Regular Expressions (PCRE) was written, a library in C - used extensively by R, PHP, Nginx, Apache - a library with regular expressions powerful than that inscribed in the POSIX standard.

Fast-forward to today, and regular expressions are used extensively in text processing programs, text editors and are a part of standard library of many programming languages, available as a library for others (crates, for fellow Rustaceans out there). All sounds cool and good on paper - you have a syntax (which we’ll cover later) to search for practically any string out there, but *with great power, comes great responsibility.*

And thus, we come to ReDOS. Imagine that you’ve made the perfect website (with centered divs), you’re using industry-favourite Cloudflare for DDOS mitigation, and your system comes to its knees solely from one user’s well-crafted input. Well, that’s ReDOS or Regular Expression Denial of Service for you. You wouldn’t be the first one it has happened to - for the Internet has always been kind enough to maintain archives of everything that has happened. Details of the Cloudflare outage on July 2, 2019, How I Fixed Atom?, Malformed Stack Overflow Post Chokes Regex, Crashes Site and so on. How is Regex responsible for this?

Doxxing the ReDOS

Our journey begins with a fork in the road. We’ll travel the road taken by the most, and leave the road not taken for awhile. I’m talking about implementation of the Regex parser, the way Perl and thus PCRE, Javascript, Java 8 (fixed beyond Java 9), Python and most languages (except Golang and Rust, which we’ll cover later) implement it is somewhat flawed - and there’s a reason why. And, it has to do with the history and evolution of Regex :).

To get started, I’ll quote Russ Cox’s excellent article.

The simplest regular expression is a single literal character. Except for the special metacharacters

*+?()|, characters match themselves. To match a metacharacter, escape it with a backslash:\+matches a literal plus character. Two regular expressions can be alternated or concatenated to form a new regular expression: ife1matchessande2matchest, thene1|e2matchessort, ande1e2matchesst. The metacharacters*,+, and?are repetition operators:e1*matches a sequence of zero or more (possibly different) strings, each of which matche1;e1+matches one or more;e1?matches zero or one.

Above mentioned syntax is a subset of the traditional Unix regular expressions syntax. Perl and TCL beyond added more and more operators and sequences - almost all of which can be well described by a combination of these metacharacters. TCL also introduced backreferences. Backreferences like \1 or \2 which reference the string matched by a previous paranthesized expression. For instance, (dhsrtn|ansh)\1 matches dhsrtndhsrtn or anshansh but not dhsrtnansh or vice-versa. This backreference support is the exact issue plaguing today’s regular expressions 🙏.

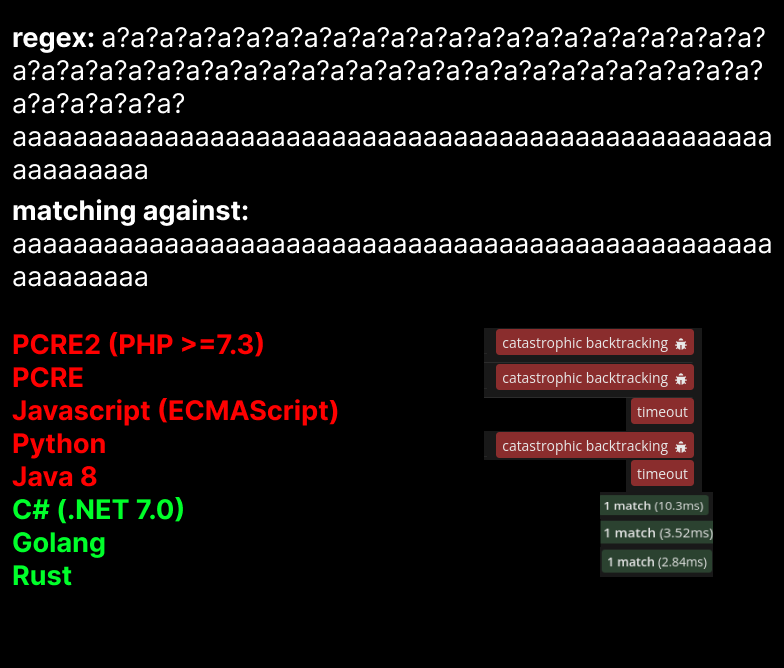

To give additional proof, here’s a regular expression that matches aaa...59 times using a regex of the form a?a?...aaaa... 59 times each.

The matching was done using regex101.com. The above given regex is an example of a pathological regex, which refers to the kind of expressions that most implementations are vulnerable to. Regex matching is done by converting the expression into finite-state automata (if you happened to complete your BTech in ECE from NITT, you’d know sequence matching experiments. We’re going to do exactly that), first - following which several possibilities exist. We’ll go through all of them with detailed illustrations in the next section.

The matching was done using regex101.com. The above given regex is an example of a pathological regex, which refers to the kind of expressions that most implementations are vulnerable to. Regex matching is done by converting the expression into finite-state automata (if you happened to complete your BTech in ECE from NITT, you’d know sequence matching experiments. We’re going to do exactly that), first - following which several possibilities exist. We’ll go through all of them with detailed illustrations in the next section.

A Class on Finite State Automata

Finite State Machines or Finite State Automata are a mathematical model that represents a system with a limited number of states. FSMs are often used in computer science and engineering to design, analyze, and implement systems.

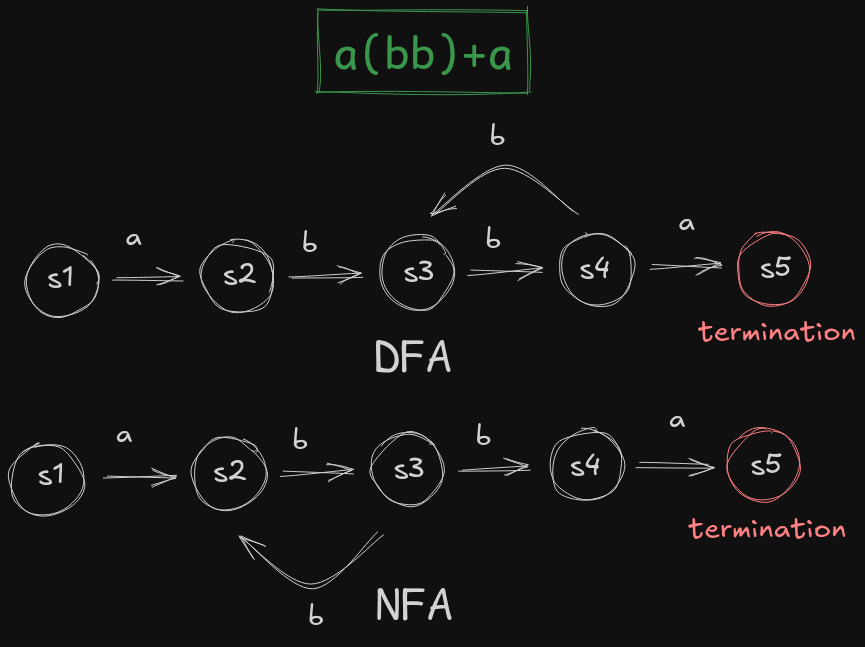

Basically, FSMs help us visualize a system with a finite number of states, and the corresponding transitions between the systems. For example, here’s an FSM model of a machine that helps us parse the regex a(bb)+a. This regex matches abba, abbbba, abbbbbba and so on. To break it down, a exactly matches a, (bb)+ matches 1 or more sets of bb, and then the ending a exactly matches an a. I’ll try my best to explain the underlying theory and lead to better articles wherever possible.

The DFA (Deterministic Finite Automata) described above has a deterministic response to each input it receives, at the initial stage s1, on receiving an a, it transitions into s2, then on receiving b it transitions into state s3, and so on. At s4, if it receives an a, it goes into s5, and if it receives a b, it transitions back to s3. A DFA accounts for every possible state in a transition.

The NFA (Non Deterministic Finite Automata) described is an equivalent but indeterminate precisely at s3, on receiving b as an input, it can either go to s4 or to s2. The NFA can also be expressed as an unlabeled arrow from s4 to s2 denoting that at s4, the machine can choose to try and parse an a or randomly return to state s2. When parsing a string, both possibilities are possible and it’s not possible to know the correct one without having prior knowledge about the input, hence the machine must choose between multiple possible next states. See where this is going?

Both are equivalent as far as representing a machine is concerned. Why would you prefer one over the other? The answer is that NFAs are more compact, but require worse time complexities since you have to try additional paths, whereas DFAs require more space complexity since you have to express multiple states. Classic space v/s time tradeoff.

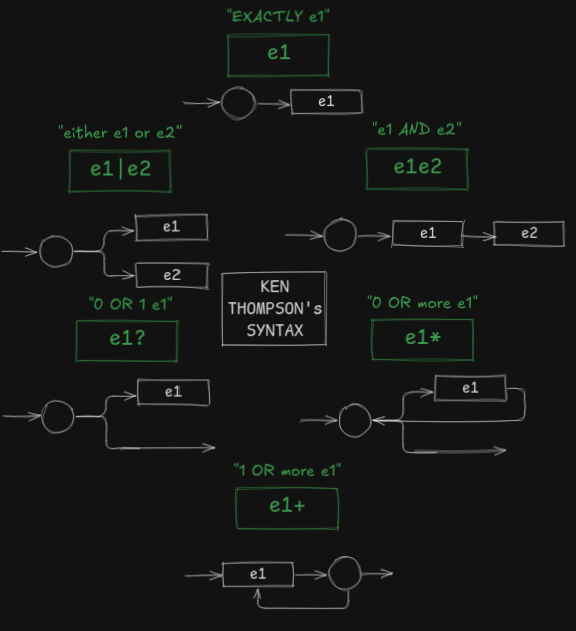

Ken Thompson, the man behind Regex as mentioned earlier - quoted a method to convert all regular expressions to their corresponding NFAs in his 1968 paper titled Regular Expression Search Algorithm. Each NFA is built up from partial NFAs for each sub-expression. Don’t worry if it seems very complicated, the accompanying description in plain-text should make it a bit easier.

After building the automata, several algorithms exist.

After building the automata, several algorithms exist.

- Try to convert it into a DFA, and pass the input to a DFA machine.

- Try all possible paths in the NFA machine, backtrack on failure.

- Try all possible paths in the NFA machine, parallely.

- Try to convert it into a DFA lazily (do it when a match happens).

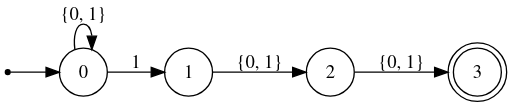

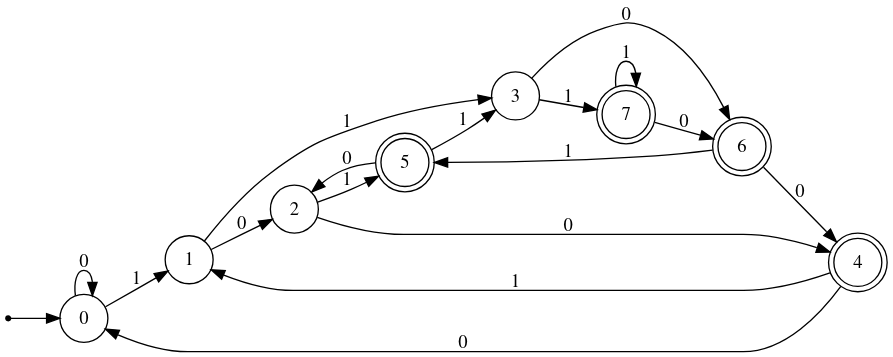

The first two are problematic. For example, consider an example of (0|1)*(0|1)(0|1). We’ll make an NFA for that, followed by the corresponding DFA.

NFA

DFA

Credits to Owen Stephen’s article for the above two images. See the exponential blow up in states? We went from 4 states, to 8. I’m cherry-picking a bad example here, for most cases the conversion will not result in so many states, but these corner-cases is what results in catastrophic failures. See this Owen Stephen’s article for more.

Credits to Owen Stephen’s article for the above two images. See the exponential blow up in states? We went from 4 states, to 8. I’m cherry-picking a bad example here, for most cases the conversion will not result in so many states, but these corner-cases is what results in catastrophic failures. See this Owen Stephen’s article for more.

Issue with the first algorithm is precisely this exponential blow-up in stages, and issue with the second algorithm is exploring multiple paths. A DFA is like a look-up table, whereas an NFA is like a recursion problem where you have to backtrack and explore multiple paths. With an NFA, you cannot say that there’s a match or there’s no match without trying all possible paths. If you encounter a match early, good for you - or you’ll be stuck trying paths again and again for a long time. At the same time, constructing an NFA is easier than constructing a DFA - NFAs are easier to understand and express the Regex pattern in a way that’s very intuitive and easy to understand. Just see the above example.

Time to talk about The Road(s) Not Taken!. The third algorithm trying all possible paths parallely does not mean doing parallel computation using multiple threads, it handles multiple states by maintaining two arrays clist, nlist respectively representing the number of states the machine is currently in, and the number of states it can be in, in the next stage. It consumes an input, checks the clist array and based on that adds corresponding successive states in the nlist, swaps both the lists and continues this loop. At any point if the current list contains the final termination state, the machine stops execution. A very rudimentary implementation can be found here in <400 lines of C.

First two algorithms have an exponential time complexity, where as the third algorithm runs in quadratic complexity. The fourth algorithm has a similar complexity where the DFA is built on-the-fly and on a on-demand basis. Here’s a note from Rust’s implementation.

We implement an online DFA. That is, the DFA is constructed from the NFA during a search. When a new state is computed, it is stored in a cache so that it may be reused. An important consequence of this implementation is that states that are never reached for a particular input are never computed. (This is impossible in an “offline” DFA which needs to compute all possible states up front.)

In the newer versions of Rust, this functionality is available via a flag on the regex crate (which is enabled by default).

This begs the question - if the third/fourth algorithm exist in the practical world and are manifolds faster, why aren’t they used more frequently? And out of all examples we’ve seen, why only Golang and Rust use the faster algorithms? Onto the next section we go!

Modern Regex

Modern regex differs from what it originally was due to which the use of third/fourth algorithms proves to be difficult. Blame Perl/TCL for introducing complexities, but most of them are actually useful in parsing text. There are two types of complexities involved here - one is just syntactical sugar like [a-f] is syntactical sugar for (a|b|c|d|e|f). Then there’s repetition. e{3, 5} literally means “match atleast 3 e, but no more than 5”, which can be expressed as eeee?e?, similarly e{3} expands to eee, and e{3,} expands to eee+.

The other type of complexities refer to complications that do not break down into primitive operators like above or are something entirely different. For example, modern regex implementations allow submatch extraction. When regex is used to split a string, through the use of $1 and $2, you can access submatches of the matched string (example - awk). Although difficult to implement using the NFA/DFA algorithms, it was finally implemented in Unix Eighth Edition. The nail in the coffin actually comes from backreferences Implementation of backreferences efficiently is an NP-Complete problem. The strategy adopted by the original awk or egrep/grep -E was the simplest - do not implement backreferences at all. Eventually backreferences became a part of the POSIX standard, and thus most languages chose to adopt a recursive approach towards regex to cater to backreferences. A clever implementation could chose to use the third/fourth algorithms to compute regular expressions w/o backreferences and resort to the recursive algorithm for backreferences, but modern implementations like Google’s RE2 (on which Golang’s implementation is based), and even Rust’s implementation still choose to chuck them for the sake of performance. Although that too comes at a cost, for backreferences have tremendous usage potential. For instance - matching HTML tags. <(.*)>*</\1> matches HTML tags along with their content. The /1 refers to the content captured by the capturing group (.*), so it matches <b>Delta Force</b> but not <b>Delta Force</a>.

Conclusion

With that we draw to an end. Regular expressions represent a fascinating intersection of theoretical computer science and practical programming. Whether you’re writing a simple validation script or designing a large-scale text processing system, knowing the potential performance implications of your regex can mean the difference between an elegant solution and a potential system vulnerability. The differences in implementations of regex engines across languages shows that there’s still significant innovation possible in how we approach pattern matching and text parsing using regex. Few might argue that the article cherrypicks bad examples to prove the most common implementations wrong - however, given between two implementations, one that works fine for most and has a backup for one specific feature and one that is error-prone and caters to all features, what would you prefer? Note that we aren’t talking about minor errors, we’re talking about errors that can bring down entire systems. Thanks for staying till the end fellow reader :)